The Cooloola Great Walk Ecotourism Project

The Cooloola Great Walk Ecotourism Project (CGWEP) is a proposal being advanced by the Queensland Government, in conjunction with the local Kabi Kabi indigenous group and a commercial “cabin style” accommodation provider (CABN) to provide for an enhanced bushwalking experience, or “ecotourism experience” in the Cooloola Recreation Area, part of the Great Sandy National Park.

The project consists of walking the Cooloola Great Walk, a 100km walking trail through the Cooloola Recreation Area with overnight stops in ecotourism cabins at five sites.

The Queensland Government is represented in this development by the Department of Environment and Science and the Department of Tourism, Innovation and Sport.

More information on the Government proposal is available on the tourism dept website.

Cooloola Recreation Area, Great Sandy National Park

The Cooloola Recreation Area is a large sand mass with varied natural environments located between Noosa Heads and Rainbow Beach and is a designated Recreation Area under the Recreation Area Management Act 2006.

The Cooloola Recreation Area, in conjunction with the K’Gari (Fraser Island) Recreation Area makes up the Great Sandy National Park.

Protected areas and National Parks

Both recreation areas and national parks are types of “protected areas” in Queensland. Protected areas are a mix of State-owned and managed protected areas, Indigenous-owned national parks jointly managed by Traditional Owners and Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service, and privately owned and managed nature refuges including those owned and managed by Indigenous peoples. They are addressed by the Queensland Government’s Protected Area Strategy 2020-2030 which identifies a long-term strategy of increasing protected areas to 17% of the State’s land mass.

National Parks are a particular type of protected area with a focus on nature conservation.

Regulation of National Parks

National Parks are regulated under the Nature Conservation Act 1992

(The Act) which set out for example, the objective of the Act, management principles, the meaning of conservation, Chief Executive powers etc.

National Parks are managed by the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service, a division of the Department of Environment and Science, according to the management principles for the specific protected area.

The Objectives of the Act

The objective of the Act as set out in s4 is:

The object of this Act is the conservation of nature while allowing for the involvement of indigenous people in the management of protected areas in which they have an interest under Aboriginal tradition or Island custom.

However, the objectives of an Act are broad statements of intent, they do not control other parts of the Act. They are used often when needing to deal with ambiguities but cannot override any other section where the legislative intent is clear. See this Australian Law Reform Commission article which states:

“Whilst regard may be had to an objects clause to resolve uncertainty or ambiguity, the objects clause does not control clear statutory language”.

The Cardinal Principle

According to the Act, National Parks are to be managed according to the Management Principles set out in s17 of the Act:

(1) A national park is to be managed to—

(a) provide, to the greatest possible extent, for the permanent preservation of the area’s natural condition and the protection of the area’s cultural resources and values; and

(b) present the area’s cultural and natural resources and their values; and

(c) ensure that the only use of the area is nature-based and ecologically sustainable; and

(d) provide opportunities for educational and recreational activities in a way consistent with the area’s natural and cultural resources and values; and

(e) provide opportunities for ecotourism in a way consistent with the area’s natural and cultural resources and values.

(2) The management principle mentioned in subsection (1)(a) is the cardinal principle for the management of national parks.

As can be seen from the above there are a range of management principles set out, including the preservation of nature, presenting natural and cultural resources, providing educational and recreational activities, and ecotourism.

However, the first principle on the preservation of nature is described in the legislation as the “cardinal principle” for managing national parks.

Cardinal principle is not defined it the Act, but in plain English means “rule or quality … that is considered to be the most important.”. Thus, preservation of nature is the primary managing principle for national parks.

Prior to 1975 national parks were managed by the Department of Forestry and often competing commercial activities were allowed in national parks such as the grazing of cattle and commercial fishing. With the introduction of the National Parks and Wildlife Act as amended in 1982 and then the new Act in 1992, nature preservation was made the primary or the “cardinal” principle. This ensured grazing, fishing and other uses which are not ecologically sustainable are excluded from national parks (covered in second reading speech in 1992 p 4922) .

There is no further guidance on how the interaction of these management principles is to be managed, and there is limited case law on their interpretation. However, we can look to previous management decisions for some guidance on their use. Under these principles we have recreational use of our parks including camping spaces, walking tracks, access roads, toilets blocks and showering facilities. We also have some examples of other types of buildings in our national parks, such as the kiosk in Noosa National Park.

Any decision on a particular facility would mean weighing the principle in the management principles and considering the impact on nature conservation and sustainability.

This issue has been discussed by Peter Ogilvie, President of the Wildlife Preservation Society of Queensland in an article:

The [cardinal] principle clearly establishes that the primary purpose of national parks is nature conservation, with other uses being subordinate to that purpose. It has been the foundation for the exclusion of activities involving introduced species (for example, cattle grazing and horse riding) and the establishment of facilities, such as tourist resorts, which are not consistent with protection of an area’s natural resources, a term that is defined to include all plants, animals and all non-living components of the landscape.

How the Act facilitates the CGWEP

For the proposed CGWEP there will be installed accommodation cabins and support buildings at sites along the walking track. These sites would be leased to the ecotourism project operator under s35 of the Act.

(1) The chief executive may grant, make, issue or give a lease, agreement, licence, permit or other authority over, or in relation to, land in a national park if—

(a) the use under the authority is only for a service facility or an ecotourism facility; and

(c) if the use under the authority is for an ecotourism facility, the chief executive is satisfied—

(i) the use will be in the public interest; and

(ii) the use is ecologically sustainable; and

(iii) the use will provide, to the greatest possible extent, for the preservation of the land’s natural condition and the protection of the land’s cultural resources and values; and

(2) Subsection (1)— (a) has effect despite section 15

Under these provisions the Chief Executive (the Director-General of the Department) may lease land in a national park to an ecotourism operator.

This power has effect despite the cardinal principle (subsection 2 – section 15 applies the management principles, including the cardinal principal to national parks). The ecotourism project must meet the standards set out in (1)(c) above. As you can see section (iii) is a copy of the cardinal principle from the management principles.

The ecotourism operator could be an individual, a not for profit, an indigenous organisation or a commercial business, there is no restriction on the type of operator.

Note that this provision is only required for an ecotourism accommodation facilitated by the leasing of land. It could be implemented in another manner, by, for example, by the Government directly building accommodation facilities (as it has done for other facilities, such as toilets) although any such facility would need to be under the cardinal principle.

How the Act has been changed over last decade by succeeding Governments

The 2011 version of the Act had a simple objective:

The object of this Act is the conservation of nature.

When the Newman Government came into power in 2012, they amended the legislation to provide for an expanded objective for the Act:

The object of this Act is the conservation of nature while allowing for the following—

(a) the involvement of indigenous people in the management of protected areas in which they have an interest under Aboriginal tradition or Island custom;

(b) the use and enjoyment of protected areas by the community;

(c) the social, cultural and commercial use of protected areas in a way consistent with the natural and cultural and other values of the areas.

In this they inserted “commercial use” as an objective of the Act. They also amended the management principles. In 2013 the management principles were:

17 Management principles of national parks

(1) A national park is to be managed to—

(a) provide, to the greatest possible extent, for the permanent preservation of the area’s natural condition and the protection of the area’s cultural resources and values; and

(b) present the area’s cultural and natural resources and their values; and

(c) ensure that the only use of the area is nature-based and ecologically sustainable.

By 2014 they had been amended to include new principles:

17 Management principles of national parks

(1) A national park is to be managed to—

(a) provide, to the greatest possible extent, for the permanent preservation of the area’s natural condition and the protection of the area’s cultural resources and values; and

(b) present the area’s cultural and natural resources and their values; and

(c) ensure that the only use of the area is nature-based and ecologically sustainable; and

(d) provide opportunities for educational and recreational activities in a way consistent with the area’s natural and cultural resources and values; and

(e) provide opportunities for ecotourism in a way consistent with the area’s natural and cultural resources and values.

Peter Ogilvie, President of the Wildlife Preservation Society was quite critical of the changes made at that time:

Why has the Newman Government chosen to comprehensively neutralise nature conservation and its associated legislation in Queensland, particularly in relation to national parks?

The Palaszczuk Government had an election commitment for the 2015 election to:

Ensure that protected area estate is managed in accordance with the cardinal principle to preserve and protect natural conditions, cultural resources and values to the greatest extent possible.

(source: Progress report on 2015 government election commitments 2020, page 74)

The Palaszczuk Government amended the Act so that it now states the objective of the Act is:

The object of this Act is the conservation of nature while allowing for the involvement of indigenous people in the management of protected areas in which they have an interest under Aboriginal tradition or Island custom.

However, the management principles in the current legislation are the same as the 2014 Act.

At the time of the amendments the National Parks Association of Queensland approved the Governments amendments however they stated that further reforms were needed on ecotourism:

NPAQ recommends that provisions for ecotourism facility within national parks be removed from the Act. The concept of tourism facilities (eco or otherwise) in national parks has not been fully reviewed, and the potential impacts not thoroughly investigated. More importantly, tourism facilities are incompatible with the cardinal principle of national park management.

Queensland Government position on ecotourism

The Queensland Government had laid out its rationale for ecotourism as follows:

- Tourism is a $23 billion industry for Queensland.

- Experiencing nature is a primary motivator for both domestic and international visitors in Australia.

- Queensland has a natural competitive advantage in providing visitors with high-quality ecotourism experiences because of our world-class national parks and marine parks, five World Heritage areas, and a huge diversity of unique and unrivalled landscapes and iconic wildlife.

- The Queensland Government is committed to progressing new best-practice iconic ecotourism experiences to attract further growth in the domestic and international visitor market.

- These Queensland Government initiatives will be fundamental to making Queensland the number one ecotourism destination in Australia, delivering world-class ecotourism attractions and experiences in Queensland’s national parks.

The Queensland Government has several polices on ecotourism development:

- Towards Tourism 2032: Transforming Queensland’s Visitor Economy Future – 2022

- Implementation Framework: Ecotourism facilities on national parks – December

- Best practice development guidelines: Ecotourism facilities on national parks – December 2020.

- Ecotourism Plan for Queensland’s Protected Areas 2023–2028: Redefining ecotourism in a contemporary landscape

However, when the Queensland Audit Office tabled an audit of ecotourism in Queensland in May 2023, it made as its first recommendation:

We recommend that the Department of Tourism, Innovation and Sport and the Department of Environment and Science, in consultation with the Department of the Premier and Cabinet, develop an overarching state-wide policy position on ecotourism for both on and off protected areas that:

- clearly defines ecotourism, and the scales and types of ecotourism development acceptable to the state

- identifies the state’s priorities for ecotourism opportunities both on and off protected areas. This should include any differences in priorities and tolerances for developments within and outside national parks while respecting the cultural and traditional ownership of First Nations people

- sets a clear direction for achieving the vision of Queensland becoming a world leader in ecotourism, providing improved consistency and clarity for government entities, industry operators, and potential developers in understanding and implementing government’s ecotourism priorities.

What leases and ecotourism projects are there in and around our parks

There are some old tourism facilities operating in our national parks:

- Lizard Island resort, built on Lizard Island National Park based on lease to private operators dating back to at least the 1970 (there was significant litigation over the building of the resort in 2002).

And some new:

The Government is working on trails in national parks:

- Wangetti Trail – in Mowbray National Park with five “eco-accommodation nodes”

- Cooloola Great Walk – in Great Sandy National Park with five “eco-accommodation camps”

- Paluma to Wallaman Falls Trail – in the Paluma Range National Park

More details here.

As well as ecotourism inside our national parks, there is also ecotourism alongside our national parks, without intruding into the national parks themselves.

- O’Reilly’s – set in private land surrounded by Lamington National Park

In May 2023 the Government announced that it would be funding six new ecotourism projects, although none appear to be in National Parks:

- The refurbishment of the Turtle Sands Nature Retreat at Mon Repos

- A luxury walkers’ camp on freehold land at Binna Burra, adjacent to Lamington National Park

- An outdoor tourism hub in the Pioneer Valley near Mackay

- Construction of Jarramali Indigenous Rock Art stays on Cape York

- An upgrade of the Carnarvon Gorge Holiday Park including new ecotourism accommodation and restaurant with a renewable power system

- Nature-based luxury glamping pods and eco-lodgings with conference, events and beach club facilities on South Stradbroke Island

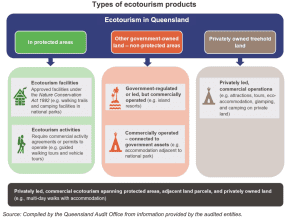

These different types of ecotourism were categorised by the Audit office in their report:

The key elements of the CGWEP

Our understanding of the CGWEP is there are three main components/parties:

- The State Government of Queensland as represented by the Department of Environment and Science (incorporated Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service) and the Department of Tourism, Innovation and Sport. They are leading the development of the project.

- CABN as the proposed commercial ecotourism operator. CABN was announced as the preferred proponent for the project on 22 February 2020, following the completion of an open expression of interest and request for detailed proposal, however they have not yet been appointed as the ecotourism operator.

- The Kabi Kabi indigenous peoples. The Kabi Kabi have a native title claim over the area of the CGWEP through the Kabi Kabi First Nation Traditional Owner Native Title Claimant Group. The government has consulted with the claimant group about the project and its cultural impacts. Other aspects of Kabi Kabi involvement in the project is also covered in the ILUA (see CGWEP FAQ).

State government involvement in the CGWEP

The State Government is the “lead” in arranging the CGWEP and is manager of the land on which it may occur (that may change or be altered by the settlement of the Native title Claim).

The State Government departments involved in the CGWEP maintain pages on the project:

- Department of Tourism, Innovation and Sport CGWEP page

- Department of Environment and Science CGWEP page (FAQ)

About CABN

CABN is a commercial accommodation service provider who also build their own cabins, which are general off-grid “tiny home” style cabins in rural areas. Currently CABN have locations in five regions in South Australia.

This is what the cabins look like in other sites where CABN have installed them.

(Source: Broadsheet)

Michael Lamprell, the Chief Executive Officer and founder of CABN was Interviewed by Noosa Today where he said about the process:

“We are broadly focused on the bigger picture of what the future looks like for Kabi Kabi, the programs we’re building with them, the broader opportunities for capacity-building, tourism training and much, much more. Our shared vision with Kabi Kabi, when executed, will show that we’ve taken the right steps from the start and will continue to do so. I’d like this project to draw attention to the whole environment of the Cooloola coast in a positive way and I think we can help in education and protection”.

Indigenous involvement with the CGWEP

There are currently no specific details in public domain yet provided regarding the involvement of Kabi Kabi in the commercial operations of the accommodation, and/or management of the national park and cultural, heritage and natural conservation guidance, training, tours or any other activity. This would be expected once a submission has been made to DES for the project, and from the Prescribed Body Corporate (PBC)

The Kabi Kabi Native Title Claim

In 1992, the High Court of Australia handed down its decision in Mabo v Queensland where the court found that the common law of Australia recognises rights and interests to land held by indigenous people under their traditional laws and customs as long as traditional laws and customs continue to be observed, unless the rights were otherwise extinguished by an incompatible grant by the Crown.

The Paul Keating Government created a clear legal process for native title claims through the Native Title Act 1993 which also established the National Native Title Tribunal to provide mediation, assistance and registration for native title claims.

The Kabi Kabi First Nation Traditional Owners Native Title Claim Group has applied for Native Title since 2013, with a revised and merged claim registered in 2019. The claim covers the areas specified below in the claim map:

(Source: National Native Title Tribunal)

The claim covers all of the Cooloola Recreation area in the Great Sandy National Park (and therefore all of the CGWEP).

In the native title claim the claimants are represented by the Queensland South Native Title Services, which is a public legal service, funded by the Commonwealth to represent native title claimants. As a legal service it works for the native title claimants only.

The Queensland government is represented by the Department of Resources as the manager of State land.

Some examples of previous registered native title claims in national parks:

- Butchulla people – K’Gari – transfer of 22 hectares freehold (media release)

- Waanyi people – Boodjamulla (Lawn Hill) National Park – transfer of national park to Waanyi people and lease back to Government (media release)

The native title claim is important component of the CGWEP as the Native Title Act imposes conditions on the parties to a claim (i.e., the State Government with respect to the claim over the site of the Cooloola Great Walk):

A great deal of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (NTA) concerns itself with ‘future acts’. A future act is something that is intended to be done by parties other than the claimants or native title holders on or with land (or waters) in such a way as to cause impact to native title rights and interests.

Section 24AA goes on to say that a future act will be valid if the parties to an Indigenous Land Use Agreement (ILUA) agree to the act being done and, at the time the act is done, the ILUA is registered.

(source: PBC website, more information see also Native Title Tribunal)

The Indigenous Land Use Agreement (ILUA)

ILUAs are voluntary agreements between native title claimant groups and others about the use of land under the Native Title Act. They can be made before, during, or after native title claims are determined.

They can be used, for example, to resolve smaller or narrower issues separate to the much larger and more complex native title claim.

An ILUA has been registered for the CGWEP. The Agreement is between the Kabi Kabi Peoples Aboriginal Corporation (a registered Indigenous Corporation), represented by P&E Law, and the State of Queensland (acting through the Department of Tourism, Innovation and Sport and the Department of Environment and Science).

The ILUA describes key aspects of the CGWEP, particularly that the project covers the establishment, construction, maintenance, operation, repair and decommissioning of:

- infrastructure, such as signage, associated with commercially guided walks along the Cooloola Great Walk by the Ecotourism Operator;

- associated ecologically sustainable hiker eco-accommodation facilities located at five separate locations (“Sites”) within the Assessment Area in the vicinity of the Cooloola Great Walk, but limited to:

- (i) 10 cabins (each of no more that 38m2 in area) and a communal facility at each of two sites, and

- (ii) 6 tents (each of no more than 24m2 in area) and a communal facility at each of three other sites.

It describes the sites for the eco-accommodation and describes the process for appointing an Ecotourism operator.

Prescribed Body Corporate

A “Prescribed Body Corporate” is terminology used in the Native Title Act to describe the indigenous organisation that is a party to a native title agreement.

The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Studies maintains a website on PBCs which states that:

The NTA and the PBC Regulations say that when a positive native title determination is made, the native title holders must nominate a corporation – known as a Prescribed Body Corporate (PBC) – to hold or manage their native title rights and interests. The NTA also requires PBCs to be recorded on the National Native Title Register once the native title determination is made. Once this occurs the PBC becomes known as a Registered Native Title Body Corporate (RNTBC)

The PBC Regulations say that to be a PBC, a corporation must:

- be registered under the Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006 (CATSI Act) (see ORIC and CATSI Act)

- limit its membership to native title holders (or people who the native title holders have consented to)

- meet the ‘Indigeneity requirements’ under the CATSI Act, which essentially require the majority of directors and members to be Indigenous peoples

- list the purpose of acting as a Registered Native Title Body Corporate in the ‘objects’ of the corporation’s Rule Book

- Most importantly, the PBC Regulations also require PBCs to consult with and obtain consent from native title holders before making decisions that affect native title rights and interests.

As the ILUA is a registered agreement, the ILUA designates:

“PBC” means Kabi Kabi Peoples Aboriginal Corporation ICN 8996.

The Kabi Kabi Peoples Aboriginal Corporation is register by the Register of Indigenous Corporation (no 8996).

As the native title claim is still only a claim and not settled there is no settled PBC and the indigenous party to the claim is the Kabi Kabi First Nation Traditional Owners Native Title Claim Group as set out in the claim.

Government indigenous engagement policy

The Department of Environment and Science DES Gurra Gurra Framework provides the policy for the Departments engagement with indigenous groups. The Framework states that the vision is:

- To walk forward together, from two paths to one, in a partnership founded on respect, trust and First Nations peoples’ vision for Country and people.

And then provides for a range of principles in how this vision will be achieved, for example:

- recognising that First Nations peoples are the Traditional Owners of Queensland irrespective of determination of Native Title

- understanding and supporting the journey towards cultural proficiency

- Focused on material issues and initiatives that are pragmatic and deliverable

- working in partnership from the earliest stages of development through to implementation and evaluation

- working together to define outcomes and benefits

- empowering First Nations leadership

- structurally enabling co-governance and co-stewardship

- respecting community-led decision-making processes and timeframes

- exploring new ways of working through co-design and co-delivery.

Current status of the CGWEP

At present the general parameters of the CGWEP (such as the sites) are known, the ILUA associated with the project has also been agreed between the State Kabi Kabi Peoples Aboriginal Corporation, and the ecotourism operator has been proposed (CABN) but not appointed.

However, as far as we are aware there are a number of aspects of the project that have not yet determined:

- the contractual agreed ecotourism operator has not been appointed.

- there is no lease agreement with the the Department to lease the land at the sites for ecotourism accommodation.

- We do not know the nature of the arrangements between the Kabi Kabi and the ecotourism operator and State Government on the role of Kabi Kabi in the project (beyond the limited information in the ILUA).

Advocacy on indigenous involvement CGWEP

We have received in our office an amount of advocacy regarding the CGWEP.

Some have raised the issue of which indigenous people are involved in the Native title claim and ILUA – this is governed by Commonwealth Government legislation in the Native Title Act 1993.

Other have questioned how extensive the indigenous involvement is in the project. The Department have stated that they have engaged with the indigenous representative up to this time and we have reported on this involvement in this Noosa360 article from last year. At this point we can only take on face value the departments commitment to indigenous involvement through their indigenous involvement strategy referred to above.

As to whether the level of involvement of the indigenous representatives amounts to “genuine” involvement, this needs to be deferred to the indigenous representatives to assess and inform us of their consideration of the nature of their involvement in the project.

Having said that, the nature of the arrangements for indigenous involvement has not been agreed at this time and no ecotourism operator has been appointed.

Advocacy on nature conservation in the CGWEP

We have received advocacy over what types of activities should be allowed in our national parks and the ways to constrain or ban different types of activities.

This has often been related to the Nature Conservation Act and the operation of the Cardinal Principle.

Various options have been presented to limit activity in our natural parks for purpose of nature conservation include banning commercial activity in National Parks, banning the leasing of land in our national parks, either totally or for commercial activity, or banning permanent accommodation structures.

Next Steps

When we receive further information on any developments in the CGWEP we will update via Noosa360 and provide notification through social media.

We have requested but have not yet obtained a Kabi Kabi factsheet with more detail on the next steps from the Department of Resources after a meeting in March. It is still with Queensland South Native Title Services, however once received, we will update via Noosa 360 and notify via our Friday night update on Facebook.

We have also requested that the PBC once elected, meet with our community to discuss the proposed project, and answer any questions from our community.

We are also conducting a poll on views of the different types of activity that should be banned/allowed in our national parks and the results will be published when the poll is completed.

We will also be updating this post with additional information and FAQs which we expect to be ready next week.

Further

Public submissions may be made to DES regarding any and all aspects of the Cooloola Great Walk Project, associated State approvals, and lease conditions (including an appropriate lease term). Any submissions received will be considered as part of its assessment should an application for the Cooloola Project be made by the proponent, and as part of the Chief Executive’s decision-making process should the project progress to final approval. Submissions can be made to DES at any time via this email (ecofacilities@des.qld.gov.au).

For the Noosa 360 history on this, please head to www.sandybolton.com/?s=Cooloola+Great+Walk